Pauline Maniraguha Bangirana, one of the four surviving female police pioneers, recounts how it was mandatory for a policewoman to ask for permission to get married.

Maniraguha, who was in pioneer cohort of 10 females to join Uganda Police Force in 1960, says although male police bosses could allow a policewoman to get married, it was always an abomination for the logical outcome of marriage -getting pregnant – to happen.

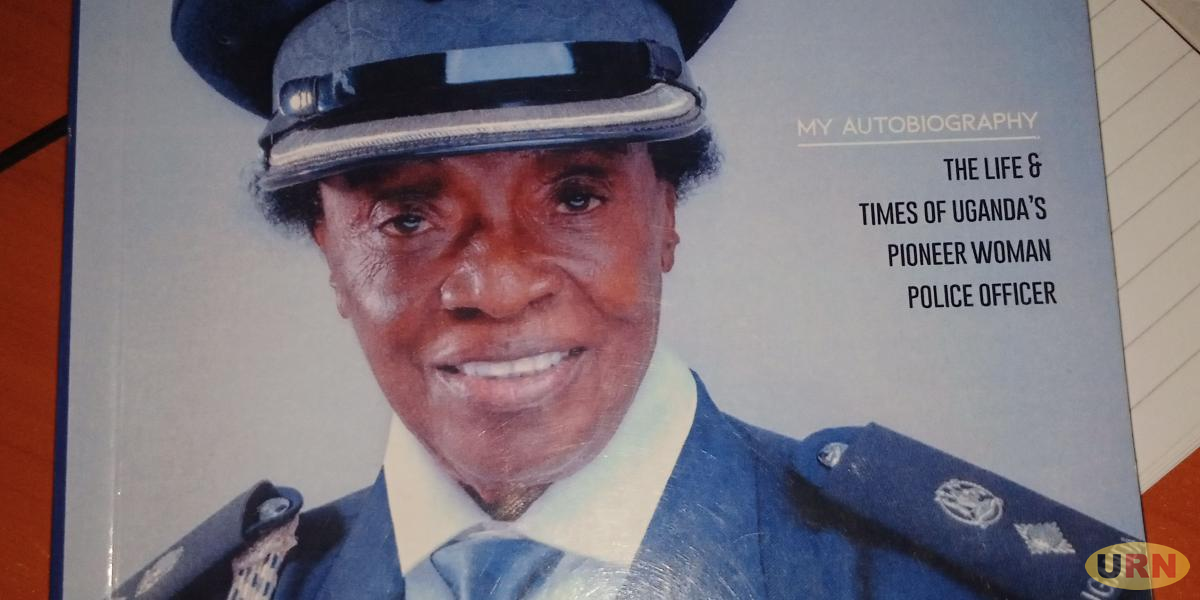

In her autobiography, which she intends to launch in the coming few weeks, Maniraguha narrates that pregnancy was always enough to show policewomen the exit from the force. In 1965, Maniraguha applied for marriage and her request was granted. A number of her seniors include her immediate boss who she refers to as ‘Sir Richard’ attended the wedding at Christ the King Church.

But the joy her immediate bosses exhibited at her wedding twisted when she reported her pregnancy six months later. Sir Richard recommended to the (pioneer African) Inspector General of Police, Erinayo Wilson Oryema, that she needed to resign.

Sir Richard based his argument on Police Standing Order Chapter 3 which stated that if a pregnant female police officer refused to leave the force on her accord, the police would dismiss her. The commandant was however sensible enough to give her a copy of the recommendation he had made to the IGP.

“I wrote to Mr Oryema begging him to consider my case compassionately” Maniraguha recounts. “I pointed out the fact that he allowed me to get married and the result of my marriage was pregnancy. I also showed him Chapter 30 of the PSO which stated that if a woman police was pregnant and wished to resign, she would be discharged at her own request.”

Oryema granted her annual leave of 36 days plus 90 days of unpaid leave. Maniraguha says her resilience and standing force her rights was one of the reason why treatment of female police personnel has tremendously evolved over the years.

Unlike today where police women are holding command positions, Maniraguha says that back then Women Police section was just an integral part of the force. Females would be recruited purposely to handle children and women who conflicted with the law.

“They trained Women Police to take statements from women and children or juveniles who were victims of rape, defilement, incest and indecent assaults. They also charged women with the responsibility of searching and escorting younger persons and women suspected to having committed offences,” Maniraguha states.

Maniraguha walks with her head high that due to their stand against the unjust treatment of Women Police, today senior women police are assimilated into the mainstream of the force and entrusted with administrative positions.

She spent a big part of her career in police as an investigator and handled some of the biggest political conspiracies that shook the country over the years, including under the NRM administration, which make her book an interesting and eye-opening read.

Now aged 79, Maniraguha also tips young female officers on how they can tell off their Commandants making sexual advances without appearing rude and embarrassing them. This, she says, she learnt from Ms Robinson, who she met at Kennington Police Station in United Kingdom in 1964. Ms Robinson had earlier been in Uganda at the time when Maniraguha was recruited and she flew back after her three years’ tour of duty.

While there, Maniraguha asked Ms Robinson how she handled sexual advances from Senior Police Officers. Robinson told her that a Woman Police should be shrewd without appearing a shrew. The book’s title is derived from that valuable piece advice. “If a Senior Officer asked a young woman police for a relationship, she had to say that she was already engaged and that she contemplated marriage.”

Maniraguha says that advice worked for her throughout the time she served in the police force and it is the reason she got married to a civilian Polycarp Bangirana.

Maniraguha was enticed to join police force in September 1960 by her sister Patricia and brother in-law Mr Ayigihugu (the deceased famous lawyer) after they saw an advert in English Newspaper known as Uganda Argus. The advert asked women aged 18 to 21 years who were single or divorced to join police.

She at first was not enthusiastic about police since she wanted to be a Community Development Assistant. Mr Ayigihugu took her to the recruitment officer where she was given to sheets to write an application and a composition stating why she wanted to join police force. The rest was history. She rose from one rank to another, becoming a top investigator, until she retired as a Superintendent of Police.

-URN