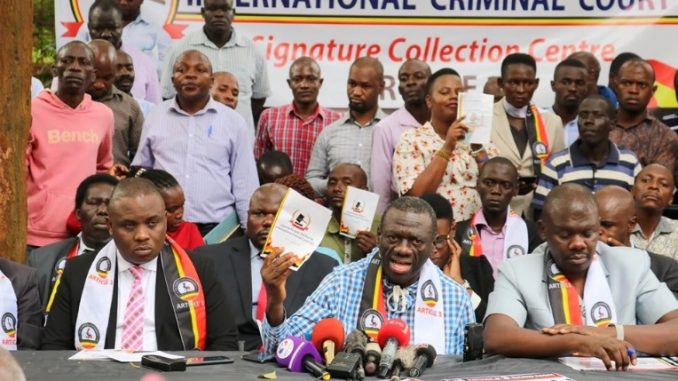

On Tuesday, Uganda’s opposition kingpin, Kizza Besigye launched a petition to gather signatures and have the country’s President Yoweri Museveni indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

According to the opposition’s so called ‘Peoples Government’ that Besigye leads, they hope to have Museveni and other government officials dragged to the Hague based court set up in 1998 to try some of the most heinous crimes committed by individuals and groups.

Besigye and co want to gather two million signatures to convince the court that Uganda’s leader may be a candidate of the ICC.

It is not the first time members of the opposition are attempting to drag Museveni to the court.

In the aftermath of the Kasese Palace attacks in November 2016 that claimed more than 100 lives, Kasese Woman MP and then Leader Of Opposition in Parliament, Winnie Kiiza, launched a similar campaign with the help of Kasese lawmakers.

However, the activity did not gather steam as either her colleagues in the opposition mildly shunned it.

Will the current campaign succeed and does the opposition have what it takes to cause the court that has been accused of African bias to act?

This artucle examine the scenarios under which the court whose current Prosecutor, Gambian Fatou Bensouda can determine that one has a case to answer.

THE ICC CRIMES THAT MAKE A CASE

The Court’s founding treaty, called the Rome Statute, grants the ICC jurisdiction over four main crimes.

First, the crime of genocide is characterised by the specific intent to destroy in whole or in part a national, ethnic, racial or religious group by killing its members or by other means: causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; or forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Second, the ICC can prosecute crimes against humanity, which are serious violations committed as part of a large-scale attack against any civilian population. The 15 forms of crimes against humanity listed in the Rome Statute include offences such as murder, rape, imprisonment, enforced disappearances, enslavement – particularly of women and children, sexual slavery, torture, apartheid and deportation.

Third, war crimes which are grave breaches of the Geneva conventions in the context of armed conflict and include, for instance, the use of child soldiers; the killing or torture of persons such as civilians or prisoners of war; intentionally directing attacks against hospitals, historic monuments, or buildings dedicated to religion, education, art, science or charitable purposes.

Finally, the fourth crime falling within the ICC’s jurisdiction is the crime of aggression. It is the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, integrity or independence of another State. The definition of this crime was adopted through amending the Rome Statute at the first Review Conference of the Statute in Kampala, Uganda, in 2010.

THE PETITION

For Besigye’s petition to succeed, it must meet the above requirements or it will pass as another attempt by the opposition to do what most people call time wasting activity.

The prosecutor begins an investigation if a case is referred either by the UN Security Council or by a ratifying state.

He or she can also take independent action, but prosecutions have to be approved by a panel of judges.

WHAT KIND OF CASES DOES THE COURT PURSUE

The court’s first verdict, in March 2012, was against Thomas Lubanga, the leader of a militia in the Democratic Republic of Congo. He was convicted of war crimes relating to the use of children in that country’s conflict and sentenced in July to 14 years.

The highest profile person to be brought to the ICC is Ivory Coast’s former President Laurent Gbagbo, who was charged in 2011 with murder, rape and other forms of sexual violence, persecution and “other inhumane acts”.

Other notable cases included charges of crimes against humanity against Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta, who was indicted in 2011 in connection with post-election ethnic violence in 2007-08, in which 1,200 people died. The ICC dropped the charges against Mr Kenyatta in December 2014.

Among those wanted by the ICC are leaders of Uganda’s rebel movement, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), which is active in northern Uganda, north-eastern DR Congo and South Sudan. Its leader Joseph Kony is charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes, including abduction of thousands of children.

The court has an outstanding arrest warrant for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir – the first against a serving head of state. When Mr Bashir – who faces three counts of genocide, two counts of war crimes and five counts of crimes against humanity – attended a African Union summit in South Africa in June 2015, a South African court ordered that he be prevented from leaving the country while it decided whether he should be arrested under the ICC warrant.

The South African government allowed Mr Bashir to leave and in the fallout a judge angrily accused the government of ignoring the constitution. The government in turn threatened to leave the ICC.

In 2015, the ICC began a preliminary investigation into the 2014 Gaza conflict. The Palestinian Authority submitted evidence to the court in June of what it claims were war crimes committed by the Israeli military. A UN report found evidence of war crimes by both Palestinian militant group Hamas and the Israeli military.