The 2019 Sochi summit drew almost all of Africa’s heads of state

Russia has been expanding its influence in Africa in recent years and after the invasion of Ukraine, it will be expecting its new-found allies to provide support, or at least remain neutral, in international bodies such as the UN.

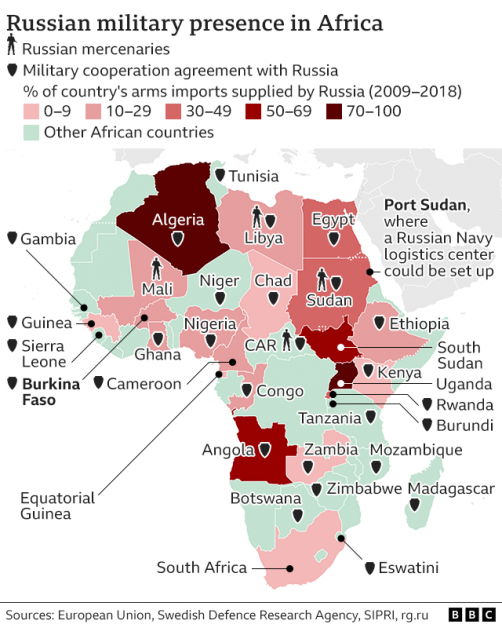

From Libya to Mali, Sudan, the Central African Republic (CAR), Mozambique and elsewhere, Russia has been getting more involved – often militarily with help fighting rebels or jihadist militants.

At the UN Security Council, Kenya, currently a non-permanent member, made its opposition to Russian action in Ukraine very clear.

But there has not yet been a loud chorus from other countries backing Kenya’s position. The continental body, the African Union, expressed “extreme concern” about what was going on, but was muted in its criticism of Russia.

South Africa, which is a partner of Russia in the Brics group, has called on the country to withdraw its forces from Ukraine but said it still held out hope for a negotiated solution.

On the other hand, CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra has been reported as backing Russia’s decision to recognise the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states.

And on Wednesday the deputy leader of the Sudanese junta, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, led a delegation to Moscow in a sign of closer ties between the two countries.

One of the clearest examples of how alliances have been shifting in Africa came just a week before Russia’s attack on Ukraine with the ending of French involvement in fighting jihadists in Mali.

Mali’s Prime Minister Choguel Maiga confirmed, in an interview with France24, that his country has signed military cooperation agreements with Russia. But he denied that the controversial Russian private military company, the Wagner Group, was involved.

This Russian help in Mali, along with a reported offer to the military government in Burkina Faso, fits a pattern over the past five years where Russia has intensified steps to increase its influence in Africa, both official and informal.

As the renewed Russia-Africa engagement gained momentum, a 2019 summit in the southern Russian city of Sochi was attended by delegates from over 50 African countries, including 43 heads of state.

President Vladimir Putin addressed the leaders, appealing to a history of backing liberation movements and pledging to boost trade and investment.

But there has also been another kind of presence: the opaque provision of security to governments in a number of African countries, in the form of training, intelligence and equipment, as well as involvement of Russian mercenaries in local conflicts.

As Mr Putin indicated, there are historic ties stretching back to the days of the USSR, Russia’s predecessor, when Africa was one of several spheres of competition between it and the US.

But from the collapse of the USSR in 1991 to the early part of the last decade, as Russia went through a period of transition, relations with Africa were not top of the agenda.

Then, regaining superpower status became a foreign policy priority for the Russian president.

In 2014, following Russia’s annexation of the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea and the international sanctions which followed, there came a sharp deterioration in relations with the US and the European Union.

Faced with the threat of international isolation, Moscow started the search for new allies.

“As a result of sanctions, Russia needed to look for new markets for its exports,” said Irina Abramova, director of the Africa Institute at the Russian National Academy of Sciences.

But it was more than markets that Russia was after – it also wanted increased global influence.

In 2014 it got involved in Syria’s civil war, backing President Bashar al-Assad in part to highlight the mess the West was making and show how Russia could fix it.

From Syria it later moved on to the African continent.

Irina Filatova, an honorary professor of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, says Russia’s key task in Africa was to discredit Western influence, in much the same way as in Syria.

It wanted to show that the Europeans, for example, had failed to contain the jihadist threat in the Sahel.

It did this through a dual policy in Africa, combining official military instructors working in some countries, and informal agencies, such as the Wagner Group, fighting in a number of others.

The CAR was the first African country where Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group appeared in 2017.

Later they were followed by an official contingent of Russian military consultants. Their aim was to help President Touadéra stay in control.

Allegations of atrocities carried out by the mercenaries have become common, but Russia has consistently denied that any of its citizens were involved in war crimes or violence against civilians.

Russian mercenaries have also been active in Libya, Sudan, Mozambique and Mali, with varied levels of success.

In another sign of the growing significance of the continent, Africa has become a key market for Russia’s arms industry. Almost half of all the arms coming into Africa come from Russia, according to the country’s state arms export agency.

The main importers are Algeria and Egypt, but there have been new markets in Nigeria, Tanzania and Cameroon.

But there is also a prize for closer ties on the diplomatic front. Africa, in total, has more than a quarter of the votes at the UN General Assembly, and can be a powerful collective voice in other international bodies.

A 2021 report on perspectives of Africa-Russia cooperation, published by Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, pointed out that African countries have tended to be neutral when it comes to Russia’s actions in the past.

“None of the African countries introduced any sanctions against Russia [after 2014]. In the voting in the UN on Ukraine-related issues, most countries of the continent express a neutral position,” the report said.

With the invasion of Ukraine, if that neutral stance continues, or if it is translated into more vocal support, then Russia’s efforts over the past few years could be seen to have paid off.

-BBC