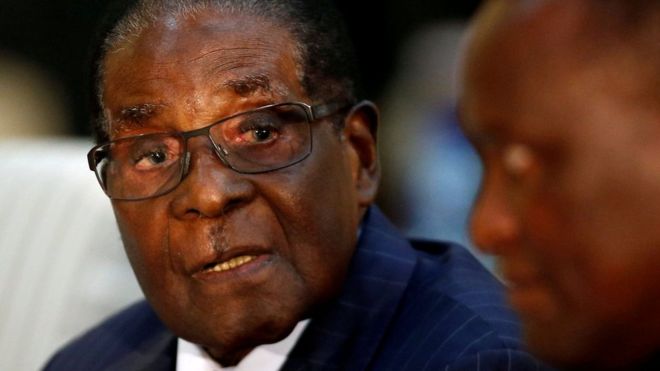

Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule is over. He resigned Tuesday as the ruling party moved to impeach the 93-year-old leader, almost a week after the military seized control of the country.

His exit clears the way for Emmerson Mnangagwa to claim the top job and for military veterans of the country’s struggle for independence to reassert their political clout.

Mugabe’s violent tenure in office included allegations of vote-rigging, human rights abuses and policy missteps that have driven what was once one of Africa’s star performers to economic ruin.

1. Was this a coup?

Not legally speaking. The armed forces were quick to say that they weren’t targeting Mugabe or his family when they took control Nov. 15.

They said their actions were directed against “criminals around him who are committing crimes that are causing social and economic suffering in the country.”

The ruling party was within its rights to order him to quit, to force him out if he refused to go and nominate a replacement. Tens of thousands of people poured into the streets of Harare, the capital, on Nov. 18 to celebrate Mugabe’s expected departure.

Mugabe ruled for 37 years — the entire existence of Zimbabwe — after the downfall of the white minority government of what was then called Rhodesia. Violent repression made Mugabe a pariah to most of the Western world.

2. What sparked the crisis?

It’s all about who would succeed Mugabe, who is the world’s oldest-serving leader and in poor health. The catalyst was the president’s decision to fire his long-time ally Mnangagwa, a pillar of the military and security apparatus that helped Mugabe emerge as the nation’s leader after independence from the U.K. in 1980. Initially, his dismissal suggested that Mugabe’s wife Grace and her supporters had gained the upper hand in the battle for control of the ruling party and the race to succeed the president. Yet the unopposed intervention of the armed forces shows where the true power lies.

3. What are Mugabe’s links with the army?

While Mugabe isn’t a military man and didn’t fight in the independence war from 1964 to 1979 that saw him come to power, the armed forces have respected his role as the commander in chief.

Constantino Chiwenga, the overall commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces who has traditionally supported Mnangagwa, joined the war for liberation in 1973 and has over the years said he won’t accept a national leader who didn’t take part in that struggle.

The military wanted Mugabe to agree to step aside so it could head off tension with the Southern African Development Community, which includes Zimbabwe and South Africa, whose president, Jacob Zuma, is the regional trading bloc’s current chairman. That group and the African Union don’t recognize governments that are installed via coups, and the military wanted to make sure that its intervention wasn’t seen as such.

4. What happens next?

The ruling party said Mugabe’s decision to fire Mnangagwa was unconstitutional and that he’ll be reinstated and then named interim president. He’ll also be the party’s presidential candidate in elections that are due to be held next year. There’s a chance that Mnangagwa includes opposition-party leaders in a transitional administration.

5. Where is Grace Mugabe?

In the days after the military seized power, she disappeared from view. Mugabe wed Grace, his former secretary, in 1996 after the death of his first wife. Nicknamed “Gucci Grace” in Zimbabwe for her extravagant lifestyle, she used her position as first lady to kick-start a political career and was elected head of the ruling party’s women’s league. Her presidential ambitions were backed by members of a ruling party faction known as the Generation-40. She’s now been expelled from the ruling party, along with a number of her allies, and her political career is almost certainly over.

6. What does this mean for the economy?

In Mugabe’s four-decade rule, the economy has deteriorated from resource-rich breadbasket to basket case. Mnangagwa’s new administration will face an uphill battle to get it back on track. Hyperinflation peaked at about 500 billion percent at the end of 2008, according to the International Monetary Fund. The nation has no currency of its own, using mainly the U.S. dollar as legal tender, and there are chronic shortages of cash. An estimated 95 percent of the workforce is jobless and as many as 3 million Zimbabweans have gone into exile. In 2000, Mugabe’s government authorized the often-violent seizure of about 4,500 mostly white-owned commercial farms to redistribute to blacks in a land-reform program that human-rights groups slammed. Exports of tobacco, the nation’s biggest foreign-currency earning agricultural product, collapsed.

7. How did the standoff affect daily life?

The military seized control of the state broadcaster sealed off parliament and surrounded the central bank. While several armored vehicles were stationed in the center of Harare, there was no sign of upheaval, most shops and banks remained open and the airport and stock exchange were operating as normal. The protests Nov. 18 were mostly peaceful. The University of Zimbabwe postponed examinations and foreign embassies warned their citizens to remain at home and exercise caution. Police roadblocks on most of the country’s major routes that were used to extract bribes from commuters have mostly been removed.

-Bloomberg