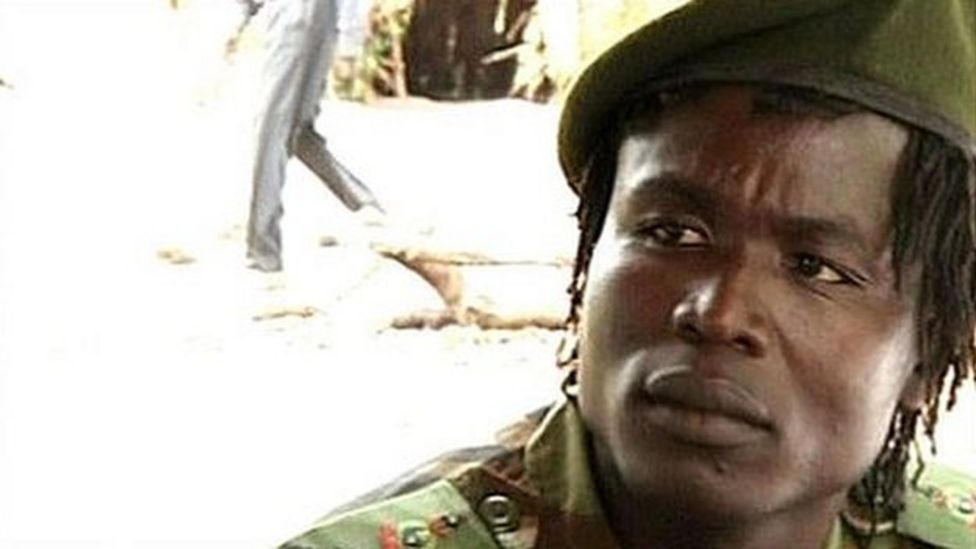

Dominic Ongwen is the first LRA commander to appear before the International Criminal Court

Known as the “White Ant”, convicted war criminal Dominic Ongwen is estimated to have been between nine and 14 years old when he was abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) as he was walking to school in northern Uganda – going on over the next 27 years to become a ruthless rebel commander.

Warning: Some people may find details in this story upsetting

“It is a story of a child, like many in the LRA, forced to grow up in the image of their oppressors,” campaign group LRA Crisis Tracker says.

Shortly after his abduction in 1987 or 1988, he tried to escape with three others and when they failed, he was forced to skin alive one of the other abductees as a warning, a psychiatrist at his war crimes trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague said.

“They skinned this person, removed his gut, and put it up on trees,” Dickens Akena told the court. “And he [Ongwen] said he wouldn’t eat meat for two to three months.”

Ongwen – whose surname means “born at the time of the white ant” – went on to rise rapidly in rebel ranks, becoming a brigadier by his late 20s after winning the confidence of LRA leader Joseph Kony, LRA Crisis Tracker says.

But he had a fractious relationship with the LRA warlord, managing to escape his clutches in 2015 when he surrendered – 10 years after he, Mr Kony and three other senior commanders had been indicted by the ICC.

He has now been found guilty of 61 of the 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed between July 2002 and December 2005.

They relate to attacks on four camps, guarded by the security forces, set up for those forced to flee their homes because of rebel raids. He was also convicted of charges relating to sexual slavery and conscripting and using children under the age of 15 in hostilities.

Claiming to fight for a biblical state, the LRA has killed more than 100,000 people and kidnapped more than 60,000 children during the three-decade long conflict which spread to several of Uganda’s neighbours.

Ongwen, who had pleaded not guilty, said he should have been regarded as a victim too, telling the court: “I’m one of the people against whom the LRA committed atrocities.”

‘He liked dancing’

Described as a quiet and playful child, his uncle, Johnson Odong, a court witness, said Ongwen’s parents were both dead within a month of his abduction – his mother allegedly bludgeoned by the rebels and his father mistaken for a rebel by the security forces.

Primary school teacher P’Atwoga Okello said in a defence witness statement that the boy enjoyed cultural dance classes “and other areas of the arts”.

His teacher in the LRA was Vincent Otti, who went on to become Mr Kony’s deputy, with whom he lived after his abduction, according to academic Erin K Baines.

A good teacher could command fierce loyalty after indoctrinating captives through brutal beatings and rituals – followed by military training and looting raids, she says.

Ongwen was reportedly eager to please, but initially struggled with the demands of life on the hoof – the long distances travelled on foot, and one ICC witness said he had to be carried across big rivers.

In the mid-1990s he moved to what is now South Sudan from where the LRA conducted operations. By 2001 he was a field commander and he became known for replenishing forces through abduction raids in Uganda, Ms Baines says.

“[He] earned the reputation of being able to emerge from the bloodiest of battles with few casualties among his fighters,” the Enough Project, another campaign group, says.

Dominic Ongwen at a glance:

- Abducted by the LRA on his way to school

- Rose to become a top commander

- Accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including enslavement

- ICC issued arrest warrant in 2005

- US offered $5m (£3.3m) reward for information leading to his arrest in 2013

- Transferred to the ICC in 2015 after his surrender. Found guilty of war crimes in 2021.

Has Joseph Kony been defeated?

One former abductee called him “a tough fighter who was always on the move” – though with a limp from a bad leg injury.

During the trial, the prosecution presented LRA radio communications intercepted by Ugandan security agencies, showing how Mr Kony – who convinced his army of abductees that his “spirits” could read their minds – kept tight command and control over his battalions.

“Successful commanders were praised by Kony and other senior officers. I remember Dominic Ongwen, referred to as Odomi, frequently being singled out for praise,” said a radio surveillance officer, whose identity was kept secret.

But Ongwen also had a volatile relationship with Mr Kony, opposing the execution of Otti in 2007 after the two fell out amid stalled peace talks.

“LRA defectors report that Ongwen was the only commander who pleaded with Kony to spare Otti’s life, a move that weakened his influence within the LRA,” says LRA Crisis Tracker.

“However, Kony spared Ongwen from the subsequent purge of Otti loyalists due to Ongwen’s value to the LRA, particularly his ability to lead troops on daring missions.”

The peace initiative took place in a jungle clearing on the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo and what is now South Sudan – with incredible footage of the rebels interacting with mediators.

With his trademark dreadlocks and boyish looks, Ongwen is seen looking on cautiously at the proceedings, which observers say ultimately failed because of the refusal to withdraw the ICC’s 2005 indictments.

For some – including his “bush wife”, Florence Ayot – this was an injustice.

“Dominic used to tell us he was abducted when he was very young. Everything he did was in the name of Kony, so he’s innocent,” she told the BBC in 2008.

Granted amnesty after escaping from the LRA in 2005, she had been abducted as a nine-year-old and first became the “wife” of LRA commander Obwong Kijura, who had raped her at the age of 13.

After his death, she told the ICC she willingly became Ongwen’s “wife” as the LRA leader would not allow women to live on their own.

She said he treated her son like his own children by his other three “wives” at the time and was never violent to her. They had two children together.

“I loved him because of the way he would live with people. He was not quarrelsome, and I felt it was good for me to go to him. There was nothing I disliked about him because I had not seen anything wrong he had done before… We lived happily together.”

‘I was screaming’

This jarred with testimony of seven others at the trial, including witness P-227, another of Ongwen’s “wives”. Abducted in April 2005, she was allegedly forced to have sex with Ongwen a month later: “I started crying, I was screaming and my voice was really loud.

“He asked why I was crying; he told me if I continued crying – he showed me his gun… I felt like my whole body was being torn apart.” She says she was repeatedly raped until her escape in 2010.

And escape was a dangerous endeavour – the LRA would threaten to destroy your village if you did so. According to Ms Ayot’s testimony, she and Ongwen did plot to go in 2003, but their plan was discovered and her “husband” was placed “under arrest” by Otti for several weeks.

Some psychiatrists at the trial felt Ongwen was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and a dissociative identity disorder at the time of the attacks on the camps, when the prosecution said was he a battalion commander in the Sinia Brigade – becoming its overall commander in March 2004.

ICC prosecutors quote witness testimony as saying that on at least one occasion he ordered his men “to kill, cook and eat civilians”.

More than 4,000 victims have participated in the trial – represented by two legal teams – most of them former camp residents – and the trial has detailed the lives lost, destruction, abductions and psychological damage to these communities in northern Uganda.

Rows over family phone calls

With reports of his killing in 2005 proving to be untrue, Ongwen remained on the run for many more years as the rebels moved west into DR Congo and its other neighbours.

In 2013, the US – which had joined the hunt for LRA commanders – offered a $5m (£3.3m) reward for information leading to Ongwen’s capture.

An LRA escapee alleged that Mr Kony ordered that Ongwen be severely beaten for insubordination at the end of 2014.

In bad shape he eventually escaped from the LRA camp in Darfur, making it from Sudan to neighbouring Central African Republic (CAR), where he was taken into custody.

At the time he asked for forgiveness from the Ugandan people, but within 10 days he had been transferred to the ICC.

According to Justiceinfo.net, during his pre-trial incarceration he seemed to enjoy his chance to pursue an education, including piano-lessons.

Though he threatened suicide and went on hunger strike in 2016 in rows over phone calls to his family – he had initially been barred from talking to his children.

Some argue that the trial has been a proxy prosecution of Mr Kony, whose rebel movement is much weaker these days but is still active outside Uganda.

Nonetheless two versions of Ongwen emerged during his trial: one of a brutal killer, the other of a traumatised child soldier who grew up to be a conflicted man.

His defence team argue he should now be sent home for local Acholi leaders to oversee justice through their traditional reconciliation rituals – as has been done with thousands of other fighters before him.

Credit: BBC