President Museveni at his farm in Kisozi

At the time of the inauguration of a new cabinet in 2016, President Yoweri Museveni, who had been in power for 30 years back then, boasted that Uganda was on the cusp of achieving lower-middle-income status.

This is a term used by the World Bank Group to refer to nation-states with a per capita Gross National Income (GNI) within a predetermined bandwidth. According to the categorisation, lower-middle-income countries have a Gross National Income per capita ranging between USD 1,036 and USD 4,045, and still struggle with the provision of basic necessities, such as clean water and food.

By 2016, the time of Museveni’s declaration, Uganda’s GNI per capita was USD 790, a 4.2 per cent decline from the status in 2015. It declined further to USD 740 in 2017, before going up to USD 750 in 2018 and USD 780 in 2019, according to macrotrends, a premier research platform for long term investors. The GNI per capita is the dollar value of a country’s final income in a year, divided by its mid-year population.

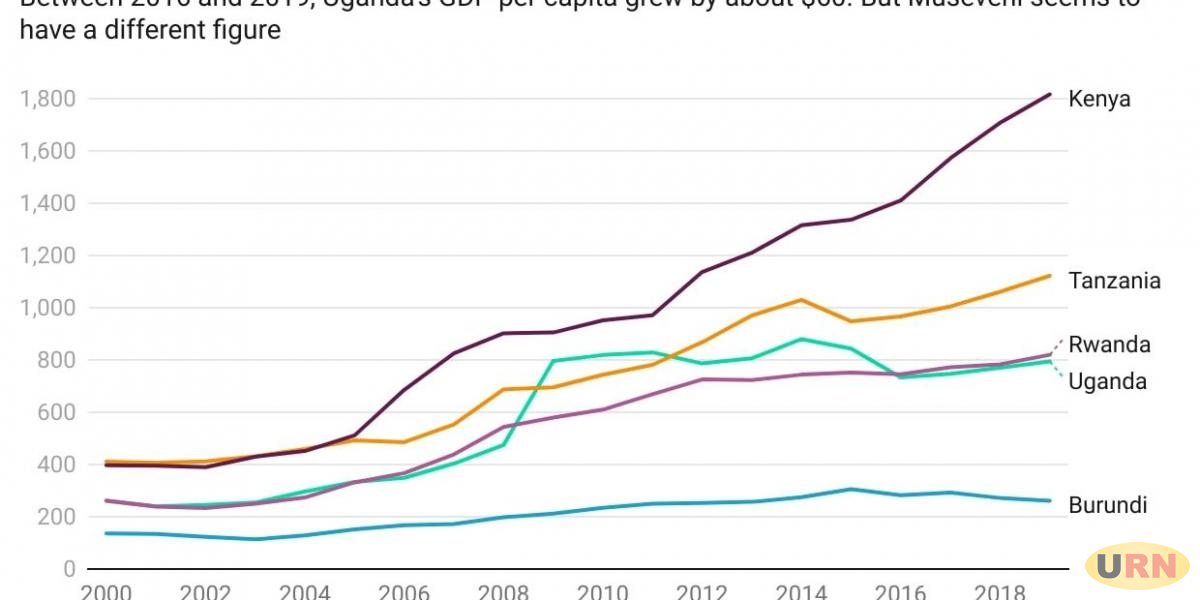

Similarly, the Gross Domestic Product- GDP per capita, measured through the economic output divided by the population, was 733 in 2016 and increased to USD 747 in 2017, USD 770 in 2018 and 794 in 2019. This is the same year that the World Bank updated its data and, according to its record, Uganda’s GDP per capita was USD 794.3 from USD 933.43 of 2016 when Museveni argued that Uganda was about to achieve lower middle-income status.

And last week, President Yoweri Museveni told the outgoing cabinet that before the coronavirus pandemic hit, the GDP rate was growing at 6.4 per cent, and the GDP per capita should have reached USD 1,000 per person but now stands at USD 900.

In the 2020-21 budget framework paper, the Ministry of Finance noted that “nationally, the budget for the financial year 2020/21 will be implemented at a time when Uganda’s population will have crossed the 41 million mark and attained an average per capita GDP of USD 905,” a figure also carried by the National Development Plan.

“When compared to regional peers for the same years (2016-2019), Uganda had the slowest GPD per capita growth except Burundi whose per capita went down from USD 282 to 261. Rwanda’s per capita grew from USD 745.3 to USD 820 which is an increase of about USD 85. Kenya’s per capita grew from USD 1,410 to USD 1,816. It has already achieved lower-middle-income status. Tanzania per capita grew from USD 966 to USD 1,122. And it also achieved middle income in 2019, according to the World Bank.

Paul Corti, a senior research fellow at Economic Policy Research Center, Makerere, a government-funded think tank, says that middle-income hopes could have been premised on oil money but production did not start in this term. “One of the missed targets was oil-driven growth which was expected. With oil, we could grow 12-13 per cent,” he says.

Corti argues that the government should not be in a rush to achieve lower middle-income status. “I think we should do things at our pace. Even if we achieved it in 20 years. We should not be in a rush,” he argues. Instead, he thinks the government should focus on growing a quality population. It doesn’t make sense to have a per capita figure that doesn’t reflect the quality of Ugandans.

But Julius Mukunda, of the Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group (CSBAG), says that it’s of urgency that Uganda attains middle-income status. “It’s like telling a patient in a hospital to grow slowly to recover,” he says, disagreeing with Corti’s argument. “We should rush to get out of this pain (poverty) that has crippled us.”

However, he warns that it will be hard to attain middle-income status with endemic corruption in Uganda and skyrocketing expenditure in areas that aren’t critical for poverty eradication.

“We have less money in areas that can get us out of poverty. For example, on average 70 per cent of local government money on budgets go to wage bills. This means a lot of money for few people, the technocrats and less money for we the people,” he says.

-URN