Investigators may never know how Covid-19 emerged in the country — and how to stop it from happening again.

In the year since seafood hawkers started appearing at Wuhan’s hospitals sickened with a strange and debilitating pneumonia, the world has learned a lot about Covid-19, from the way it spreads to how to inoculate against the infection. Despite these advances, a chasm remains in our understanding of the virus that’s killed nearly 2 million people and whipsawed the global economy: we still don’t know how it began.

Where the pathogen first emerged and how it transmitted to humans is a stubborn mystery, one that’s becoming more elusive with each passing month. Before the initial cluster among stall-holders at a produce market in central China, the trail largely goes cold, and the country the novel coronavirus hit first — the place many blame for unleashing the disease on an under-prepared world — now has little incentive to help find the true origin of the greatest public health emergency in a century.

China has effectively snuffed out Covid-19, thanks to stringent border curbs, mass testing and a surveillance network that allows infected people and their contacts to be tracked via mobile phone data. With the fight over the pandemic’s source becoming an extension of the broader conflict between the world’s two superpowers, China is now trying to revise the virus narrative from the beginning, and nowhere is that more evident than at the original epicenter: Wuhan.

As the world continues to grapple with soaring death counts and mutated strains, China is already relegating the pandemic to its version of history.

The Battle Against Covid-19 Special Exhibition seeks to memorialize everything from mask-making machines and 2,000-bed temporary hospitals to lockdown haircuts and remote learning. A timeline at the entrance to the exhibit chronicles President Xi Jinping’s virus actions in careful detail, starting on Jan. 7, when he ordered the country’s leaders to contain the rapidly swelling outbreak and ending in September, when Xi gave a speech to bureaucrats in Beijing on how China tamed the coronavirus.

There’s no mention of the Huanan seafood market, those first infections, or the public uproar over the government’s cover-ups in the early days of the epidemic, when it hid the extent of human-to-human transmission and delayed taking action. Li Wenliang, the whistleblower doctor whose death from Covid-19 sparked the biggest backlash Beijing had seen in years, appears in a lineup of other Wuhan physicians felled by the virus, barely noticeable. For many Chinese, that anger has been replaced with a sense of pride, that their country bested a crisis that’s all but defeated the U.S., leaving China stronger and on track — by at least one consultancy’s estimate – to become the world’s biggest economy five years earlier than previously predicted.

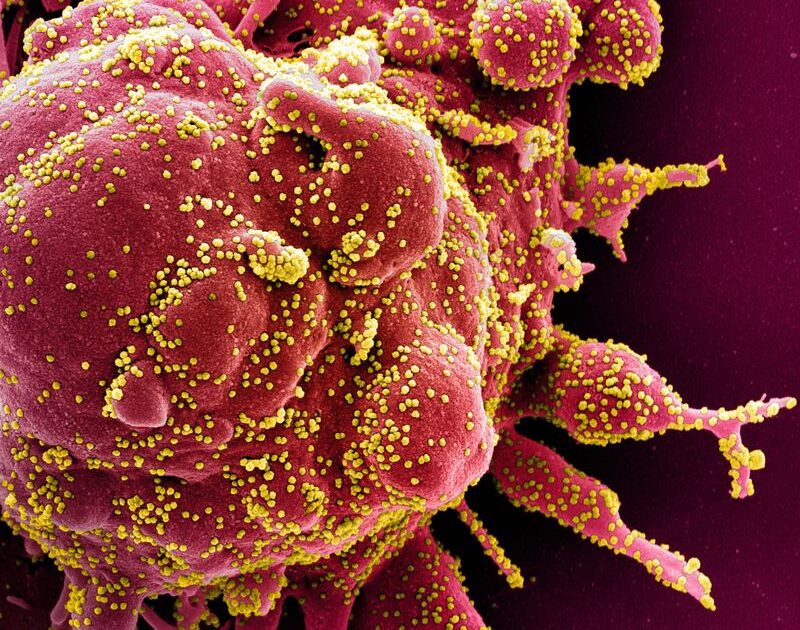

With the virus firmly contained — Wuhan has had no locally-transmitted cases since May — there’s a growing push to dispel the idea that China was the ultimate source of the virus, known officially as SARS-CoV-2. A foreign ministry spokesman has been espousing theories that link the virus to the U.S. military, and after a spate of cases in Chinese port and cold storage workers, state-backed media are claiming the virus could have entered the country on imported frozen food. They’ve also seized on research that suggests there were infections in the U.S. and Italy that pre-date those in Wuhan.

While some of these theories may have credence, the irony is that we may never know how and where the virus emerged. China has ignored appeals for an independent investigation into the virus’s origin, hammering Australia with trade restrictions after it called for one. It’s also stalled efforts by the World Health Organization to get top infectious diseases experts into Wuhan this year. That’s prevented the painstaking epidemiological detective work — from probing samples of the city’s wastewater, to checking patient specimens collected months before the outbreak appeared for early traces of the pathogen and undertaking tests at the food market itself — that could provide insight into the chain of events that brought the virus to the bustling capital of Hubei province, and how to stop it from happening again.

Now, with a WHO team focused on tracing the virus’s origin hoping to visit Wuhan in January, and a crew commissioned by The Lancet medical journal also on the hunt, the city may not have much to reveal. Life is largely back to normal for Wuhan’s 11 million people, the first to experience the lockdowns now shuttering parts of Europe and North America for a second time.

“These things are awfully hard to do retrospectively, even if all the evidence is still in place,” said Robert Schooley, an infectious-diseases physician at the University of California, San Diego and editor-in-chief of the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Located just 5 miles south of the exhibition center, the Huanan seafood market is partitioned off by eight-foot-high metal barricades, replete with pictures of tranquil rural scenes — bolted to the ground. Potted palm trees dot the perimeter of the multi-story building, site of the world’s first known cluster of Covid-19. Until government cleaners swooped in in late 2019, to close, vacate and sanitize dozens of stalls, it was a key source of produce for locals and restaurants in central Wuhan. It was also reported by media including Agence France Presse to have sold a range of wild animals and their meat, from koalas and wolf pups to rats and palm civets, the cat-like animals suspected of being the conduit of the SARS virus between bats and humans, which led to a deadly outbreak in China in 2002 that subsequently spread to other parts of the world.

Now only eyeglass vendors line the sparsely filled aisles on Huanan’s second floor, their diminished clientele carefully vetted by security guards. On a recent visit to the market, Bloomberg News reporters were warned away by plain-clothes officials and later, police.

Beyond the carefully constructed museum exhibits, few other signs of Wuhan’s epic battle with the coronavirus exist. A makeshift hospital famously built in about two weeks to treat thousands of critical patients has been shut down and boarded up. Two local women said they’d heard the site would be turned into apartments.

Wuhan Beat the Virus. Now It’s Moving on by Shutting Out the World.

In Wuhan Tiandi, a shopping precinct that claims to have China’s first outdoor food street with air conditioning, couples and families rugged up against the winter chill casually remove their face masks to eat and chat. When asked about the origins of the virus, most said it didn’t start in the city.

For all of China’s stonewalling, scientists suspect they could well be right.

The place a virus first infects a human isn’t necessarily where it begins spreading efficiently among people, said Joel Wertheim, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, where he studies the evolution and epidemiology of infectious diseases. HIV, for instance, is thought to have originated in chimpanzees in southeastern Cameroon, but didn’t begin spreading readily in people until it reached the city of Kinshasa, hundreds of miles away.

While researchers surmised early on that the horseshoe bat identified as the likely source of SARS could also have spawned SARS-CoV-2, how it crossed the species barrier to infect humans remains unclear. It’s likely that precursors to this virus spilled over from their natural reservoir many times, but went extinct when infected individuals didn’t transmit the virus to anyone, according to Wertheim. Eventually, the virus infected someone who passed it to multiple people, who also passed it on to others.

“You could have sort of these one-off, dead-end transmission chains until you get into Hubei province, which is where the epidemiological data says this is where it was spreading,” Wertheim said. “And it seems to have seeded the rest of China from there, and then from China to the rest of the world.”

Chinese scientists published the genetic sequence of the virus in January, a move that has allowed experts elsewhere to make some inroads into how this may have started. Wertheim and his colleagues studied SARS-CoV-2 virus genomes and the pace at which they mutated and diversified from the earliest known specimens in Wuhan. From mid-October to mid-November 2019 is the most plausible period in which the first case in people emerged, according to a pre-print of Wertheim’s research released Nov. 24.

The question of how the pathogen got to central China is the subject of more debate. The coronaviruses most closely related to SARS-CoV-2 were found in bats in China’s Yunnan province, some 1,000 miles southwest of Wuhan. The mountainous region borders Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar, all countries known to have sizable horseshoe bat populations.

“We can’t rule out that the person who first got this virus was in Yunnan and then infected another person who hopped on a plane and went back to Wuhan after their vacation,” said Michael Worobey, head of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona in Tucson, who worked with Wertheim on the timing of the first possible case.

Other scientists see a potential answer in outbreaks half a world away. Over the past few months, SARS-CoV-2 has exploded among mink populations in Europe and North America after the virus was introduced by infected humans, with which they share some respiratory-tract features. Millions of the semi-aquatic, carnivorous mammals, reared for their soft pelts, have been culled to purge the pathogen from farms where they have been linked to mutations in the coronavirus that some scientists said could pose a threat to vaccine efficacy.

“The mink scenario to me says, where you’ve got a large population of susceptible animals in the right conditions with a certain density, then this virus is just going to go right through it,” said Hume Field, an Australian wildlife epidemiologist who worked on the international probe that linked SARS to horseshoe bats and is a member of The Lancet’s Covid-19 origins task force.

Field discovered the source of a deadly virus that killed horses and their handlers in eastern Australia more than 20 years ago. After an exhaustive search, he eventually found Hendra virus originated in large fruit bats, known locally as flying foxes. The finding led scientists to understand what veritable virus treasure troves bats are. Besides his investigation into the origins of Hendra and SARS, Field has also helped trace the Nipah and Ebola Reston viruses back to bats.

Did SARS-CoV-2 jump directly from bats to humans, or did it spread to another animal — a so-called intermediate host — that then passed it on to people? Finding out is key to reducing the risk of secondary outbreaks and the emergence of new strains impervious to the Covid-19 vaccines now being rolled out around the world. The virus’s affinity with mink suggests wild animals from the same “mustelid” family, which includes weasels and ferrets, that interacted with coronavirus-carrying bats may have played an intermediary role, according to Field.

Mink resemble “a microcosm of what could have happened prior to Covid,” said Peter Daszak, a New York-based zoologist who is part of both the WHO and The Lancet teams trying to trace the virus’s origins. He theorizes that the virus went from horseshoe bats to people in Wuhan via wildlife that were sold in the city or people connected with that trade. In the wake of the outbreak, China said it curtailed the sale and consumption of wild animals, but the trade is difficult to police given how integral it is to cuisine and traditional medicines, particularly in the south.

Researchers with the Thai Red Cross Emerging Infectious Diseases Health Science Center catch bats during a catch-and-release program in Photharam, Ratchaburi Province, Thailand, on Dec. 11. The team collects blood, tissue, saliva and fecal samples from bats in an effort to understand the origins of the Covid-19 virus.

Since bats don’t fly regularly from southern China to Wuhan, it’s more likely the virus was propagated in civets or other susceptible animals raised on farms for sale in the Huanan market, Daszak said. In the wild, coronaviruses spread across animal species via the fecal-oral route, such as when a civet eats fruit contaminated by bat droppings.

“We still don’t really know what animals were present in that market in the beginning,” he said. “It’s quite possible there are other animals in China that were infected.”

Finding out more from those who were there will be difficult, especially a year on. Scientists still don’t know the precise source of the Ebola virus, for example, nor how the H1N1 influenza virus that swept the world in 2009 jumped from pigs into people. It’s possible the origin of Covid-19 will never be found, George Gao, the director of China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention, told the Xinhua news agency this week. “We looked for suspect animals in Wuhan, but found none.”

After the Huanan market was closed, some of its stallholders were relocated to the cavernous Sijimei food market on Wuhan’s northern outskirts. On a frigid day in mid-December, it was almost deserted of customers, but few vendors were willing to speak to Bloomberg about the events that took place 12 months earlier. A spice and condiment seller who said his family name was Xie, confirmed he’d moved from Huanan in March, but said he couldn’t remember anything that happened there. Shortly after, security guards appeared saying that foreign media were barred from filming.

The response was similar at a nearby open-air market, where other Huanan vendors had set up stalls. An attendant selling lamb carcasses confirmed the business moved there in March before he was told to shut up by his manager. Moments later, two guards appeared, saying any interviews should be cleared by the Communist Party.

Bloomberg has made multiple requests over the course of 2020 to interview key Chinese scientists, including both the director and chief epidemiologist at the country’s CDC, and the nation’s most experienced coronavirus expert, Shi Zhengli.

Shi — known as China’s “bat woman” for her intrepid, decade-long exploration and collection of viruses in bat-festooned caves — has been at the center of speculation about the source of SARS-CoV-2 since its first weeks. She operates a laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology that studies some of the planet’s worst infectious disease threats. Its location in a peri-urban industrial area about 20 miles from the Huanan market has fueled theories that the virus either accidentally escaped from the lab or, more sinister, that it was genetically engineered and deliberately released.

Shi has said the genetic characteristics of the viruses she’s worked on don’t match SARS-CoV-2 and told the state-run China Daily newspaper in early February that she was willing to “bet my life” that the outbreak had “nothing to do with the lab.” Shi is also open to “any kind of visit” to rule it out, the BBC reported Dec. 22.

Still, in a vacuum of information, conspiracy theories have taken hold, with President Donald Trump — who has repeatedly referred to SARS-CoV-2 as the “Chinese virus” — a proponent of the lab hypothesis. He said as early as April that China may have “knowingly” unleashed the pathogen, and the U.S. has criticized the country’s lack of cooperation on tracing its source. For its part, China defends its work with the WHO. It’s engaged with the body on origin-tracing in a “transparent’’ manner and WHO experts have been allowed to visit the country, Wang Wenbin, a foreign ministry spokesman, told reporters this month.

Field, who’s also a science and policy adviser for EcoHealth Alliance, a New York-based nonprofit that works to prevent viral outbreaks around the world, said it’s possible Chinese scientists are well advanced in their investigations, but fears any findings into how the virus originated — whether from China or elsewhere — will be clouded in “conspiracy cover-up talk.”

“How do we make those broadly accepted to what now seems to be quite a cynical and politicized audience?”

It will likely require a level of openness China is showing no signs of embracing.

On a recent visit to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, security staff tried to stop a Bloomberg journalist from taking photographs and video from a public road outside. One guard stood in the way of the car until police arrived. Multiple requests to visit the infectious diseases lab were denied.

Outside the city’s Battle Against Covid-19 exhibition, there are no restrictions on filming. Visitors take photos of each other popping their heads out of wooden silhouettes with holes in place of faces, the kind you see of cartoon characters at theme parks, though here it’s doctors in protective suits and gloves.

Yang Feng, a 51-year-old retiree, said she found the exhibit cathartic, a reminder of everything her home town had been through, from the almost three-month lockdown to the 3,869 people who died. “I wanted to recap the history,” she said. “Now, you can’t tell Wuhan is a city that’s been through the virus.”

But Yang shakes her head when asked where she thinks Covid-19 originated.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I really don’t know.”