Ghana’s December announcement that it was suspending debt payments to selected creditors heightened the debate over the sustainability and risk levels of African debts.

The announcement took many by surprise, that the economy was so bad it needed such drastic measures.

Lest we forget, and specifically for Uganda; Ghana is one of the youngest oil producing countries in Africa, having discovered its deposits of commercial significance in 2007, a year after the same Tullow Oil made similar discoveries in Uganda.

By 2010, Ghana was a fully-fledged oil producing country, its economy further supported by what was seen as progressive politics, boomed.

Unfortunately, in 2017, the county’s only refinery exploded and Ghana again became a net importer of refined petroleum product, spending significant amounts thereon.

Now, the government in Accra is poised to request debt relief via the G20 Common Framework programme, but wants to be assured that the negotiations will be conducted and completed in a short time.

This Framework was implemented starting early last year and targets Low and Middle Income Countries that are at high risk of debt.

However, of the low-income countries, only Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia have applied for restructuring under this framework, but their applications are finding challenges being successful.

One of the reasons is the requirement by the International Monetary fund that the country first restructures its debt, yet some of the lenders are not participating in the framework.

The delays are also attributed to lack of transparency in some debt contracts. The cash shortage in Ghana is also attributed to the decline in exports and increase in imports.

The country’s foreign exchange reserves (assets held on reserve by the central bank of Ghana in foreign currencies) have also dwindled to about 6 billion dollars, and these are only equivalent to the country’s one-month-imports.

This is a major decrease from almost 10 billion dollars at the end of 2021.

According to Finance Minister, Ken Ofori-Atta, Ghana’s debt is now bigger than the value of the economy (GDP) and almost all the revenues being collected by the government (70 to 100 percent) is going towards local and foreign interest payments.

This means all other expenditures, including salaries, social services and development projects are either stalled or being financed with more debt.

To limit the amount of foreign exchange being spent on imports, especially by oil importers, the country has now decided to use gold instead of dollars starting this quarter, so as to protect the cedi from further depreciation.

Other countries that have recently suspended debt repayments include Sri Lanka, Zambia, Argentina and Greece. Mid last year, Sri Lankan protests of scarcity and high cost of essential commodities like fuel and food, led to the collapse of the government as the president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country.

The Prime Minister who took charge of the country’s affairs blamed the economic crisis on a series of emergencies including the effects of the 2019 bombings and the outbreak of covid-19, both of which greatly impacted the revenues from tourism.

However, the International Monetary Fund and other experts blamed the government policies especially subsidies on essential commodities like fuel and food.

The government had been subsidizing fuel for years against the advice of the IMF, and by the time the Russia-Ukraine war effects high the global petroleum industry, it had the lowest prices amongst the world’s non-oil producing countries. With dwindling domestic revenues, the subsidy regime more and more relied on foreign debt.

In July, at the height of the protests, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni used Colombo as an example of a failed political policy to tackle an economic crisis, to strengthen his stance against subsidies.

“Subsidies for and removing taxes from imported products is definite suicide,” he said in one statement. “It will deplete both family savings and National Reserves, leading to the inability to pay for imports. Foreigners beyond East Africa do not accept the shilling as a unit of exchange.”

Similar views have been given by independent experts who say any government policy of subsidies must be targeted towards increasing production, and not consumption.

David Ndii, Keya Economist and lecturer at Strathmore University says even Kenya was risking going the same way by introducing subsidies on fuel and food, especially maize.

“There is no saving, the subsidies were debt finance and we were following Ghana and Sri Lanka into financial meltdown,” he says, relieved that the current government led by William Ruto has reversed former president Uhuru Kenyatta’s policy.

The countries that have decided to stop paying their debts and requested for debt relief under the different international frameworks find it as the most prudent step.

However, they also find themselves at risk of losing the trust of lenders in the future.

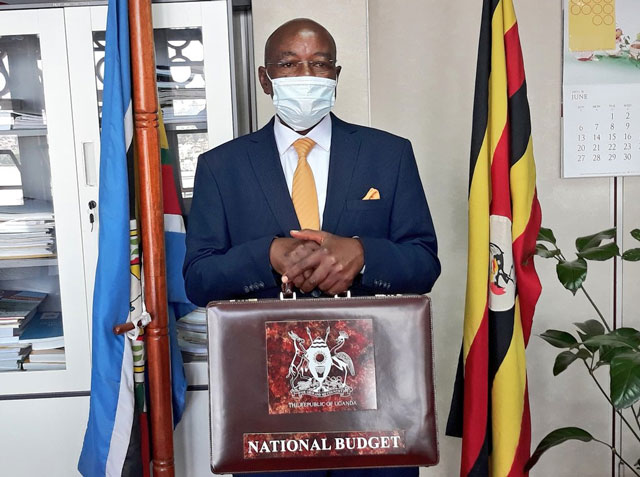

“Failure to pay debt can damage a country’s reputation with investors, making it harder for it to borrow the money it needs on international markets. This can further harm confidence in its currency and economy,” said Apollo Munghinda, Principal Communications Officer at the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development.

However, he says that the countries that have opted for this were at their worst situation, while Uganda is far from that.

“Definitely, it is not good and the team here have learnt lessons from this,’ he says.

Uganda has been listed among 10 African countries that the rise in debt could put at risk.

The others include Angola, Kenya, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Cameroon and Ethiopian according international credit rating agency, Fitch Ratings.

Uganda’s risk level was recently increased from “medium” in 2020 to “moderate”, which is a level below “High risk”.

However, the Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Finance, Ramathan Ggoobi, who says the government is continuing to put in place governance measures to manage debt better, stresses that the country is still in a comfortable position, even according to the International Monetary Fund.

Uganda seems to have survived the worst of the Covid 19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, having avoided an economic recession, according to official government records.

The African Development Bank says Uganda’s economy contracted in 2020 by 1.5 percent. This financial year, the Bank of Uganda expects a growth of 4.7 percent, while this financial year it is expected at 5 to 5.3 percent, while a long-term trend of 6-7 percent could be attained in 2025/2026.

BOU Deputy Governor, Michael Atingi-Ego says that the underperformance of the economic activity could not enable Uganda do without borrowing, but is confident that this will change in the midterm.

–URN